Now that you’ve had a chance to digest all that info in part 1 of this tour, it’s time to keep going.

After securing our candles from the street vendor, we were all ready for our evening. We ambled into an outdoor food court-type area and stopped for a bite to eat and some browsing at the vendors nearby. The girls and I stumbled onto some pretty interesting necklace charms and pins. Honestly I don’t know if it was a Colombia thing or just this vendor, but it was pretty unique. Haley and I collect very small items from each country that we fit into a small tin (think Altoids tin). Necklace charms are great for this purpose and we decided to purchase a few memorable trinkets from this rather…interesting… vendor.

Now we were finally ready for the star of the show: celebrating Dia de las Velitas with a local family. Our guides led us to the metro station and we shoved ourselves into a massively overstuffed commuter train. This was about the time people were getting off work and heading home so we were in good company. After only a few stops it emptied out and our guide was able to tell us a bit more about the neighborhood we were riding through. She told us to pay attention to the houses, as they would be different than the ones we were going to see, since they were in a different estrato. Say what?

Understanding Estratos

One thing that I find very interesting is how Colombians discuss areas of town. They use a numbered system called estrato. I think it’s best to steal from a very helpful blog called Medellin Living to explain it.

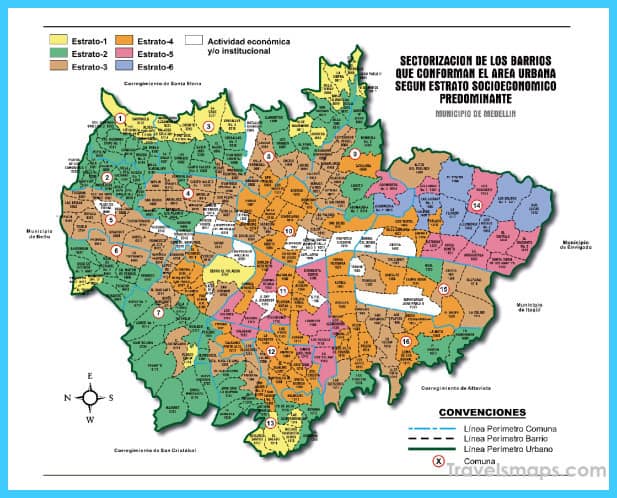

When looking at Medellín neighborhoods it is important to understand the estrato system. Residential properties in Colombia are ranked on a 1-6 socioeconomic scale (with 6 being the highest). These are known as estratos or strata. Understanding estratos is very important, as this is a factor for housing costs and also for utilities costs. Households in lower estrato neighborhoods pay a lower rate for gas, electric, water and triple play TV/Internet/phone services.

Estrato 6 is considered a wealthy area for Colombians and estrato 5 is an upper middle class area. While estratos 3 and 4 are considered Colombian middle class areas. And estratos 1 and 2 are generally poor areas. Residents in estatos 5 and 6 pay more for utilities to help subsidize lower utility rates in estratos 1 and 2.

Note that Colombian middle class is not the same as middle class in the U.S. Middle class in Colombia may be a Colombian household earning only $1,000 USD per month or even less. Many households in Colombia also have multiple people earning a living to make ends meet due to typically low pay.

In the Medellín metro area only 3.4% of homes are ranked as estrato 6 and 7.2% of homes are ranked as estrato 5. A total of 43.8% of homes in Medellín are classified as estratos 3 or 4. And 45.5% are classified as estratos 1 or 2. The vast majority of the homes in Medellín (76.4% of homes) are in estratos 2-4.

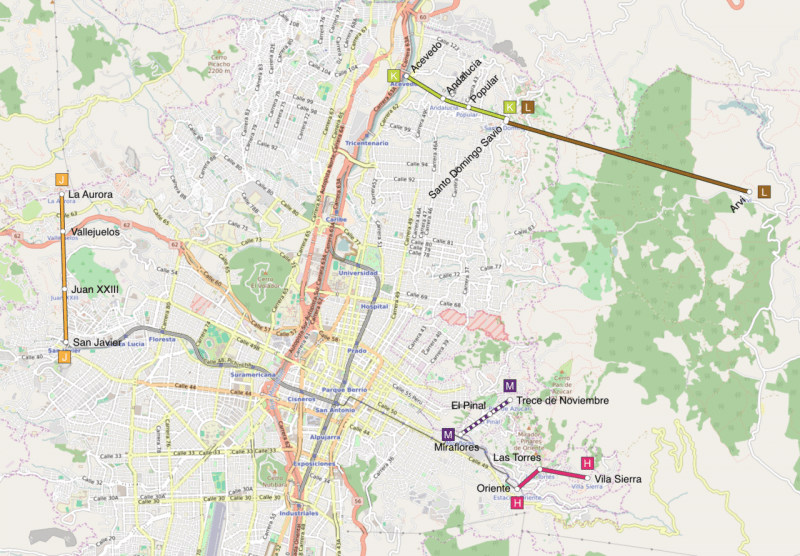

I found this image online that does not have a date on it but I think it’s from 2016. You can see the different estratos on this map of Medellin. If you see the white sections you can assume the river runs pretty much through them, somewhat through the middle of the map. The further you get from the river, the lower the estrato (generally) and the higher the elevation. One thing that, as Americans, is somewhat startling is how openly people talk about and label the different areas. The door guard was telling me about where he lived: “I have two houses, one is in estrato 2 and I don’t want my daughter growing up there, so we mostly stay in the other house which is in estrato 3 or 4.” Of course that makes sense but we aren’t used to such labels in the USA.

The Hills Are Alive Big

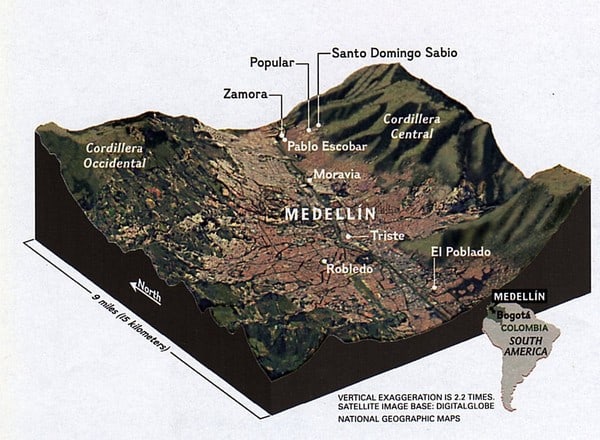

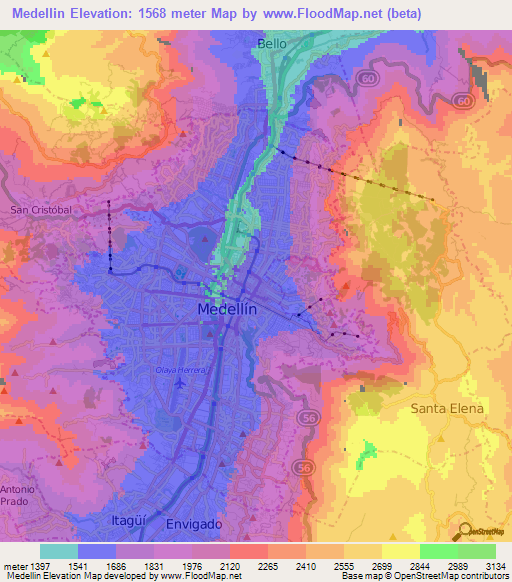

I know I keep mentioning this but you’ve got to understand the topography of this region. It’s fascinating. If you’ve watched any of the chase scenes in Narcos, you have noticed all the hills. It’s exactly like that, fer reals! Here’s some additional info because I am nothing if not thorough.

The Metrocable

OK so now you know how Colombians talk about the areas of town from a socio-economic standpoint, and you see how topography is a huge part of the city. This is now all going to come together as we continue our tour.

Our guides are easily navigating the metro train through parts of Medellin and we are just following along, hoping we’ll somehow know how to get back at the end of the night. Breadcrumbs, maybe? After a few stops we hop off and I’m expecting us to walk to someone’s house, since I knew that we were celebrating Candle Day with the extended family of one of the guides. But instead of walking to a house, we walk to a cable car and get on. WHAT? What is this? Where are we going? I assume we are going UP? Is this really a good idea? Do they know I don’t like UP? I really didn’t know what was happening at this point but we just went along. My mom taught me to be polite, even when one is scared to death of heights and cables breaking. Pretty sure that’s a commandment of some kind, maybe #11.

On the way up, in between Zoe’s gasps about how high we are, our guide explained that since Medellin is nestled into the mountains, as new people came to the city there was not enough room in the limited flat part, so expansion took place up into the hills. There was no master plan for the neighborhoods so people just built houses where they felt they could, regardless of any semblance of order or roads. Now you will find houses haphazardly placed in all kinds of different perches, accessible only by stairs or a narrow walkway, usually wide enough for a motorcycle but not a car. This makes for a difficult employment commute for the residents of La Sierra and other hillside barrios, not to mention a difficulty in getting access to one’s daily needs of food and household items.

The government decided to address this issue and added an extension to the metro system. The way they solved accessing the houses on the slope of the hill was to put in a cable car. Honestly, Medellin’s solutions to navigating these hills are so interesting. You’ll hear more about other solutions later, but for now, we were fascinated by this cable car system for these neighborhoods. Our guide tells us it’s the only cable car in the world that was installed for commuters (not tourist) use. You’ve just got to understand how this whole thing fits into the big picture so we’ll head back over to Wiki for help:

Metrocable is a gondola lift system implemented by the City Council of Medellín, Colombia, with the purpose of providing a complimentary transportation service to that of Medellín’s Metro. It was designed to reach some of the city’s informal settlements on the steep hills that mark its topography. It is largely considered to be the first urban cable propelled transit system in South America. There were plans in the city for some decades before its inception for some form of transportation that took account of the difficult topography of the region. These ideas date back to the use of cable-car technology for exporting coffee starting in the 1930s between the city of Manizales, to the south of Medellín, and the Cauca River 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) below. In its modern incarnation, it was the result of a joint effort between the city’s elected mayor and the Metro Company. For some, the initial conception of this system was indirectly inspired by the Caracas Aerial Tramway (also known as the Mount Avila Gondola) which was designed primarily to carry passengers to a luxury hotel.

Line K of the Metrocable connecting the Medellín River valley to the steep hills in Comunas (districts) 1 and 2, was the first system in the world dedicated to public transport, with a fixed service schedule. Since starting operations in 2004, it carries 30,000 people daily and is operationally integrated into the rest of Medellín’s mass transit system, which includes the overground Metro, bus rapid transit system (BRT) and a tramway line (opened in 2016).

Overall, the system has been received with enthusiasm by the locals, who are mainly low-income users and are prepared to queue for up to 45 minutes at peak times to use it. It has also served as an inspiration to a rapidly growing number of similar systems in cities in Latin America (Rio de Janeiro, Caracas, La Paz, Manizales, Cali, Bogotá, Mexico City, among others) and elsewhere.

If anyone remembers me and heights, they’ll know this ride up the mountain is not my favorite. I closed my eyes most of the way to the top and tried to ignore the various exclamations from others in our car, and the unfamiliar swaying of the vehicle as we made our way up and up and up. I was happy when we got to the station but then had to slam my eyes shut again when our guides said that this was not our stop, that we had to go up further to the top. It was a long way and very steep, for sure.

La Sierra

Once at the top we met up with some other people who showed us around their neighborhood. This is a relatively new project for them, since that cablecar was only implemented in 2016 for their area of the city. They are training to be tour guides to better illustrate life in another part of Medellin. They were so happy to tell us about some social programs they are running trying to improve life in the barrio and it was clear they relied on the Metrocable system heavily to get to work or the center of town or to do business. (Fun fact: the road up to La Sierra is only 7 km (4.3 miles) but takes 45 minute by bus due to the poor condition of the road and the endless curves.)

Some of the challenges faced by the population of La Sierra (approx 3000) include:

- kids grew up with the images of the violence in the past

- residents used to live with a daily risk of death and violence

- youth are at risk of drug addictions and influence primarily from peers

- girls are at risk of early pregnancy

Activities they are implementing to try and combat these challenges include:

- more activities within the church

- local guide training for teenagers with Bloom Travel Experiences

- new job opportunities for single mothers from the neighborhood in the kids gardens

- a group of women working on community activities (weekly sharing lunch, artisan crafts, etc)

- a new police station in the neighborhood

- new sports and public area from a community organization in Medellin

- new schools

Walking around the barrio was fascinating. There were so many stairs, steep walkways, and houses nestled into each other or the hillside. If you didn’t know where you were going you would surely be lost as there’s no discernible organization to the placement of the houses. The walkways were wide enough for two or three people side-by-side, which meant that motorcycles would be useful, although even motorcycles are limited by the stairs. The night we were there the walkways were filled with groups of people carrying candles, sparklers, drinking and just milling about. Everyone was really friendly as our large group of Colombians with a few wide-eyed gringas in the middle wandered around.

The Grand Finale: Candles and Cheeseballs

We ended up at the house of our hosts, who quickly passed out candles and showed us how to secure them to the stairs. Sparklers also came out and Zoe had a great time with the other kids who had joined us as we walked around. We chatted with the extended family, we ate traditional buñuelos (corn/cheese balls that are fried) and the sweet pudding that goes with it. Colombians are big fans of the sweet and salty combination (another reason why I feel I am Colombian in my heart) and the fact that this was gluten free was just icing on the buñuelo. Unfortunately for the niñas, the pudding had a lot of milk in it so they took a few bites to check it out but could not proceed much further.

It’s impossible to convey the level of hospitality that was shown to us on this tour. I have no idea who all these people were, but we ended up in a group of about 30 Colombians, all of whom were so happy to meet us, tell us about the neighborhood, answer questions about school, healthcare, challenges with water, electricity, internet, education, you name it. Although there was a translator, we ended up speaking mostly in Spanish, which, along with the 7+ hour tour, contributed to my fatigue as the night wore on. And I was in better shape than Haley who was still recovering from jet lag from her 3-countries-in one-week flight from Thailand to Colombia the previous week.

Around 9:30 p.m. our guide declared it was time to head back down the mountain (eek!) and we bid goodbye to our hosts and new friends. I have such a soft spot in my heart for these people, and especially as they are attempting to grow their programs by providing these tours to anyone who is interested. Harry, our tour-guide-in-training up in La Sierra, was particularly hard working and sweet and will be an amazing guide. He was born with a dangerous disease: “Hydrosefalia” (water in the brain). He managed to have surgery, but he only started to walk at the age of 4. Then, he learned to speak really late but soon he became passionate about music and singing. So he started to participate in many music talent competitions and won several. Now he’s truly concerned about the history of his neighborhood and wants to be a local guide showing the positive evolution of his home. Suerte, Harry!!! I hope you are reading this! For those of you who are now die-hard fans of La Sierra (as you should be) you can click on this link to learn more about it in this video.

On the way down I managed to open my eyes more to see the view of the city and admire the slope of the hill. By this time the girls and I are exhausted, Dan is back at the apartment wondering what the heck happened to the rest of his family, and we were all amazed by everything we had learned that day.

A quick Uber ride home and we wrapped up a fantastic day. Just because I told you all about it, that’s no reason not to do it yourself if you ever find yourself in Medellin. Or maybe by now, I’ve convinced you to actually go to Medellin on purpose. #goals