When we arrived in South Africa we were giddy that we were in an English speaking country. After more than 2 years in Spanish speaking locations it was nice to not have communication as one of the barriers. We got along pretty well in Panama, Mexico and Spain, however. Three out of four people in our family now speak Spanish well enough to navigate just about any situation and can even make a joke or two. Then there’s the 25% of the family that can order a 3-piece meal at KFC and a Diet Coke with ice and that’s about it. #guesswho

But in South Africa we were all on equal footing. No more translating Dan’s unique “very VERY well done fries” request to the waiter. Or being corrected in public by one perfectionist teen who thinks she knows Spanish grammar better than her mom. #eyeroll Or reminding the youngest that you can’t just put an “o” on the end of a word and make it Spanish. However, we soon learned that English speaking does not necessarily mean one is instantly understood. There’s still a communication gap that we have to accommodate.

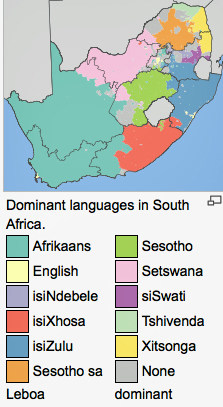

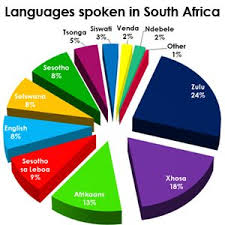

Eleven Official Languages

South Africa has eleven (!!) official languages. Indecisive, much? Well, I appreciate that they were trying to be inclusive, although if I spoke language #12 I’d be all kinds of pissed off. Eleven official languages is something that comes up a lot when you are researching South Africa as a tourist destination. It’s like a bragging right on all the tourist marketing videos. I think it’s meant to show South Africa as having a diverse culture. Well, I agree that it’s very diverse here and I appreciate that the post-apartheid government was trying to be inclusive. But many South Africans I have talked to have outlined the many challenges that exist with 11 different languages. It’s not all unicorns and skittles.

It’s Complicated

Although the tourist videos like to brag about all the languages, having lived here for 3 months we actually see it as a huge challenge to the continued viability of a healthy country. The educational system in South Africa is severely lacking and it is my personal opinion that the language challenge is a contributing factor. Here’s an article I found online that speaks to the issue from a teacher’s perspective:

Issue number one in South African education is language. The ability to read English, which is South Africa’s primary language of education and trade, is crucial for success at school (and beyond). Every single school subject employs a learner’s ability to read. Yet in my experience working at two private schools in Soweto (learners pay roughly $200 per year to attend) I have discovered that learners are not being prepared to succeed in reading. The average Grade 2 learner cannot name the letters or their sounds, and most of the Grade 3 learners cannot read English at a Grade 1 level.

There are 11 official languages in this country: nine African languages, English, and Afrikaans. Not a single one of the students I work with speaks English as their home language. Obviously, this creates a problem. Learners’ first year of school is supposed to be taught in their home language, but in a place like Soweto, where members of every regional ethnic and linguistic group can be found, it is virtually impossible to achieve this tricky task. Most of the township schools cannot afford readers for the children, let alone the salaries of teachers who could specialize in each of the various tongues.

Surely, the effect of this language barrier is to put non-English-speaking learners at a huge disadvantage, but perhaps more importantly, it devalues the importance of reading and literacy in the learners’ early years. The DOE study supports this first point. It concludes that learners who are instructed in the same language that they use at home scored on average 37% better on standardized tests than those who are instructed in a second or third language. This is a huge margin.

The second point, that the language barrier actually devalues the importance of reading and literacy in the learners’ early years, is less objectively obvious. Because the learners are taught in home language during their first year, and it is expected that they will be taught in English the following years, little progress is made in learning how to read in their home language. Why spend the time teaching a child to read in Zulu when he will be asked to read English in a matter of months? There are a number of other factors that add to the difficulty of creating a solid literacy foundation in Grade 1, including limited written materials or literacy curriculum in the African languages, low expectations surrounding home language literacy, and Grade 1 classes that are in fact quite linguistically mixed.

When a learner reaches Grade 2 unable to name letters or sounds in any language it becomes a race against time. Because learning to read is difficult for a child, reading habits form very early. If a child does not expect reading to be a part of his or her schooling in the early years, it is difficult to change that expectation. Also, children’s books are written to the level of life experience of their target audience. An alphabet book, written for the attention span and interests of a 5 year old, is not going to compel a Grade 3 learner. Programs in adult literacy often run into this same problem.

An additional but equally important element of the language barrier is that children are learning to speak English at the same time they are learning to read. If you have ever tried learning a foreign language, you know how hard it is to make sense of new words. All of these problems are palpable in the classrooms where I’m working and they make the teachers’ job (themselves not native English-speakers) incredibly difficult. Their solution? Consciously or not, teachers have devalued the importance of reading and literacy in the curriculum. Each class spends about 2 hours per week on literacy, does virtually no homework in the subject, is unfamiliar with the inside of the library (though there’s not much to see there anyway), and rarely reads anything with the children or encourages them to do so either. On balance, a more successful school that I visited spends at least an hour per day doing reading and literacy work, assigns homework each night, visits the library weekly, and reads together often.

There are other problems with education in South Africa, but the language barrier is absolutely critical to understanding why so many students are failing in school. While it is economically and logistically impossible to ensure that every learner is taught in his home language, it is possible to do a better job of prioritizing reading in the early years than schools are currently doing. This would make a huge impact on learners as they proceed to higher and higher levels of expectation. (source: https://gautango.wordpress.com)

That is one of those issues where you just shake your head and go “Wow. That’s really complicated”. We say that a lot here in South Africa. It’s beautiful, it’s fascinating, it’s complicated.

Updating Our Vocabulary

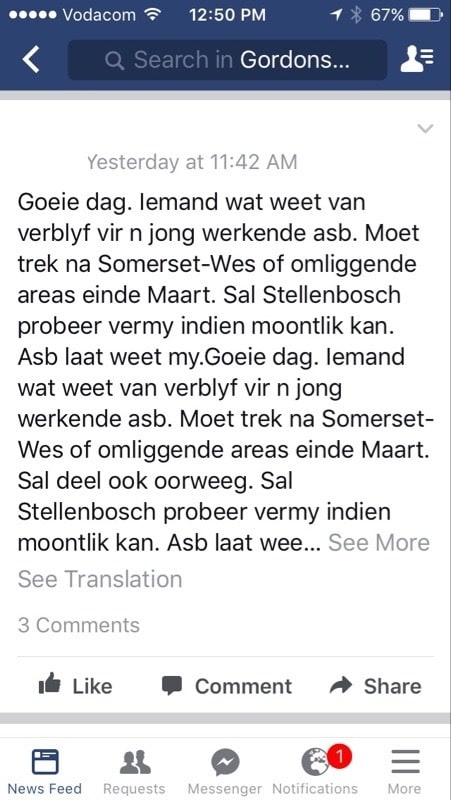

English is essentially a second language to almost everyone we’ve met… whether they be black, white or colored (that’s an actual racial category here… seriously). English could even be a a third, or even fourth language. They actually don’t even put them in any numerical order because most people didn’t learn them one at a time. The thing that is strange, for us anyway, is that you have no idea what language people might speak by looking at them. In our previous countries we would always have English spoken to us when the person could speak it. They knew by looking at us that English was our first language. Even in Spain when we might be mistaken for Dutch or German, Spaniards still spoke English when they could. Here, we are spoken to in Afrikaans.

Afrikaans is the language we hear most often after English, in the white population. Although, most everyone speaks at least some Afrikaans, no matter what color you are. However, the black population will typically speak to each other in their mother tongue and to whites in Afrikaans or English. Although it’s impossible to know who speaks any particular language until you ask. Afrikaans is the language that was created after the European settlers came. It’s essentially a branch off the Dutch language and has a lot of K’s and vowels and syllables. When we go into a store or are in line and someone speaks to us, they tend to start in Afrikaans. The accent still carries the same accent as if they were speaking English, so it takes us a moment to try and figure out if they are speaking English, or Afrikaans, or something else. The blank stare we give them is usually long enough for them to switch into English.

However, even English can be hard to understand for our untrained ears. For one, not everyone has the same English accent. Especially if they happen to speak relatively softly and/or swallow their words (which is common). They don’t seem to be aware of this trait and even when we are clearly struggling with the accent, they don’t tend to slow down or speak any more clearly. English spoken by black people tends to be harder to understand than English by white people. For all of these reasons, we tend to just go in and order when there is a drive thru because it’s just easier to communicate when they can actually see the dumbfounded look on our faces.

Although we’ve been able to communicate fine overall, we do notice that they have a lot of different words for things. Here are a few things we’ve noticed about the English here:

- HI – when we walk into a store, we say “hi”. Evidently Americans are the only ones who say “hi” and now that I’ve been told this I notice it everywhere. It’s automatic for me, but everyone else says “hello”. So that gives us away immediately. Usually after we say “hi” they want to talk about Trump.

- STEEL WATAH – They don’t call it bottled water here. They call it “still water”. I guess the still means not sparkling. But the stereotypical South African accent is true: they pronounce it STEEL WAHTAH. Therefore we have to say it that way too.

- BOOKING – You don’t make a reservation, you make a booking

- TAKE AWAY – They do not use the phrase “to go”, they say “take away”. This is complicated when they remove your plate after dinner:

Waiter: “Do you want me to take this away?”

Dan: “Yes, take it away”

Waiter: “Okay. I’ll bring it right back.”

Dan: “No, we don’t want it ‘take away'”

Waiter: “So I should leave it?”

Dan (exasperated): “Ugh… I do not want this food in front of me nor do I wish to take it to my home!”

- DOUBLE NUMBERS – When reading a number if there are two in a row that are the same they say “double #”, like “double 5”. They don’t say “5, 5”.

- PAUSE AND ACKNOWLEDGE – When reading a phone number there is a very specific way to do it. Three numbers, pause, wait for acknowledgement, three more numbers, pause and wait, then the last 4 numbers. If you deviate from this system you will probably have to start over. But you MUST acknowledge it. You can’t just stay silent waiting for the rest of the number.

- ZED – I know this is a Canadian thing too but they say the letter “Z” like “Zed”. And since all their domain names end in .za, that’s a lot of “zed” during commercials, especially when they’ve got to say their website 5 times during the commercial.

- BOSS – Men use “boss” the way we might use “sir”. Even between strangers, someone might call Dan “boss”. The guy who bumped into him while walking into the store said “Excuse me, Boss”. This does not seem to happen between two white men, only between black and white men. It seems to be an indication of deferment that is perhaps a hold over from a bygone era. Not sure. Just an observation. It’s happened on many occasions.

- WINNING – I hear this phrase a lot: “Are we winning?” or “Are you winning?” It’s kind of like “How are you doing?” It’s asked by waiters, Uber drivers and other service people who are checking in on you or greeting you informally.

- GAS – You don’t get gas for your car, you get petrol. If you need gas you need to be holding one of those silver propane tanks.

- HOLDING THUMBS – This is what they use for good luck, instead of “crossing my fingers”.

- TEKKIES – are tennis shoes, or sneakers.

- YA and YE-EEZ – This is probably the word we hear most often. Instead of “yes” or “yeah” they say “yaw”. They say it so often I have started to say it. They also pronounce it “ye-eez”. Yaw = yeah and ye-eez = yes.

Rainbow Nation

One last little tidbit related to language and culture of South Africa… it is referred to as a “rainbow nation”. Here’s the scoop:

Rainbow nation is a term coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to describe post-apartheid South Africa, after South Africa’s first fully democratic election in 1994. The phrase was elaborated upon by President Nelson Mandela in his first month of office, when he proclaimed: “Each of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees of Pretoria and the mimosa trees of the bushveld – a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.” The many migrations that formed the modern rainbow nation.

The term was intended to encapsulate the unity of multi-culturalism and the coming-together of people of many different nations, in a country once identified with the strict division of white and brown. In a series of televised appearances, Tutu spoke of the “Rainbow People of God”. As a cleric, this metaphor drew upon the Old Testament story of Noah’s Flood, and its ensuing rainbow of peace. Within North African indigenous cultures, the rainbow is associated with hope and a bright future (as in Xhosa culture). The secondary metaphor the rainbow allows is more political. Like the primary metaphor, the room for different cultural interpretations of the color spectrum is slight. Whether the rainbow has Newton’s six colors, or four of the Nguni (i.e., Xhosa and Zulu) cosmology, the colors are not taken literally to represent particular cultural groups. (Wikipedia)

So you see, it’s never just as simple as “yay, look at our eleven official languages!” or “South Africa, the rainbow nation!”. The tourist videos are right, it’s an amazing country and we encourage people to come check it out for themselves. The people, the animals, the nature, the history, it’s all so interesting. But it’s not as simple as the videos depict. If South Africa had a relationship status on Facebook, it would be “It’s complicated”. And to top it all off, their KFC does not carry extra crispy chicken. Dan says that’s not complicated, that’s just wrong.